A (Relatively Easy To Understand) Primer on Multi-Party Computation

Background: digital signatures

Blockchains use digital signatures, which use key pairs: a private key (PK) and a public key. Through digital signatures, any person with a PK can sign transactions to spend digital currencies and, assuming the PK has access, control smart contracts. Therefore, it is crucial to safeguard PKs. Some users safeguard PKs themselves and accept the risk of theft or loss. Others trust online wallets or exchanges to protect their keys.

In both these options, the user puts all their trust in a single entity. In contrast, threshold signature schemes (TSS) require a threshold of at least two cooperating participants to produce a signature.

Both multi-party computation (MPC) and multi-signature, or multi-sig, offer these capabilities. The resulting MPC signature is interchangeable with a single-signer signature. However, with multi-sig, each party has a PK. This slight difference significantly impacts the cost, speed, and availability on blockchains. For availability specifically, each blockchain requires multi-sig support either natively or via smart contracts. Supporting these increases development efforts for each new blockchain.

MPC overview

MPC is a sub-field of cryptography allowing parties to jointly compute a function over their inputs while keeping those inputs private. Unlike traditional cryptographic tasks that assure the security and integrity of communication and where the adversary is an outside party, this model protects party member privacy from each other.

The fundamental goals of an MPC protocol are,

- Input privacy: one cannot infer any information about the private data held by the parties from the messages sent during protocol execution.

- Correctness: any subset of colluding parties willing to share information or deviate from protocol execution instructions should not be able to force honest parties to output an incorrect result. This goal comes in two flavors: either the legitimate parties are guaranteed to compute the correct output (a "robust" protocol), or they abort if they find an error (a protocol "with abort").

A threshold signing algorithm has three phases,

- Generate the key pair, split the PK into multiple secret shares, and distribute these shares between parties. Distributed key generation ensures each node only learns its share; the full key is never assembled or available in one place.

- Gather a threshold of parties and run an MPC protocol to sign the transaction.

- Verify the signature using standard signature verification algorithms.

A naive example

Three coworkers, Alice, Bob, and Carol, want to know their average salary without disclosing their salaries. The function they wish to compute jointly, then, is, .

If they had a trusted friend, Dave, who they knew could keep a secret, they could each tell him their salary. Dave could compute the average and tell all of them. The goal of MPC is to design a protocol where, by exchanging messages only with each other, Alice, Bob, and Carol can still learn the average without revealing who makes what and without relying on Dave.

Alice picks a random number known only to her and adds it to her salary. She then securely passes the result to Bob. Bob adds his salary to the first result and gives the result to Carol. Carol does the same and returns the result to Alice. Alice then subtracts the random number from the total and calculates the average salary. The parties can only learn their input and the output, the exact information they would learn if trusting their honest friend, Dave.

That's MPC in a nutshell. In practice, it's far more complex for various reasons (such as robustness in the face of collusion and malicious actors).

Example use cases

- Distributed voting

- Private bidding and auctions

- Sharing of signature or decryption functions

- Private information retrieval (allowing a user to retrieve an item from a server in possession of a database without revealing which item was retrieved)

Key pair generation with secret sharing

A system is not decentralized if one entity controls a client's PK. MPC nodes, or nodes for short, own only one piece of a PK, known as a key share. The nodes then work together using an MPC protocol to perform necessary computations.

Secret sharing protects against node failures. Secret sharing is a method for distributing a secret among a group so that no individual holds any intelligible information about the secret. However, a sufficient number of individuals may combine their shares to reconstruct the secret. Any group of (for threshold) or more can together reconstruct the secret, but no group of fewer than can. Such a system is called a -threshold scheme.

Consider the secret sharing scheme where is the secret to be shared, are public asymmetric encryption keys, and are their corresponding PKs. Each party is provided with . In this scheme, any party with PK one can remove the outer layer of encryption, a party with PKs one and two can remove the first and second layers, and so on. A party with fewer than keys can never fully reach the secret without first needing to decrypt a public-key-encrypted blob for which they do not have the corresponding PK. This problem is currently computationally infeasible.

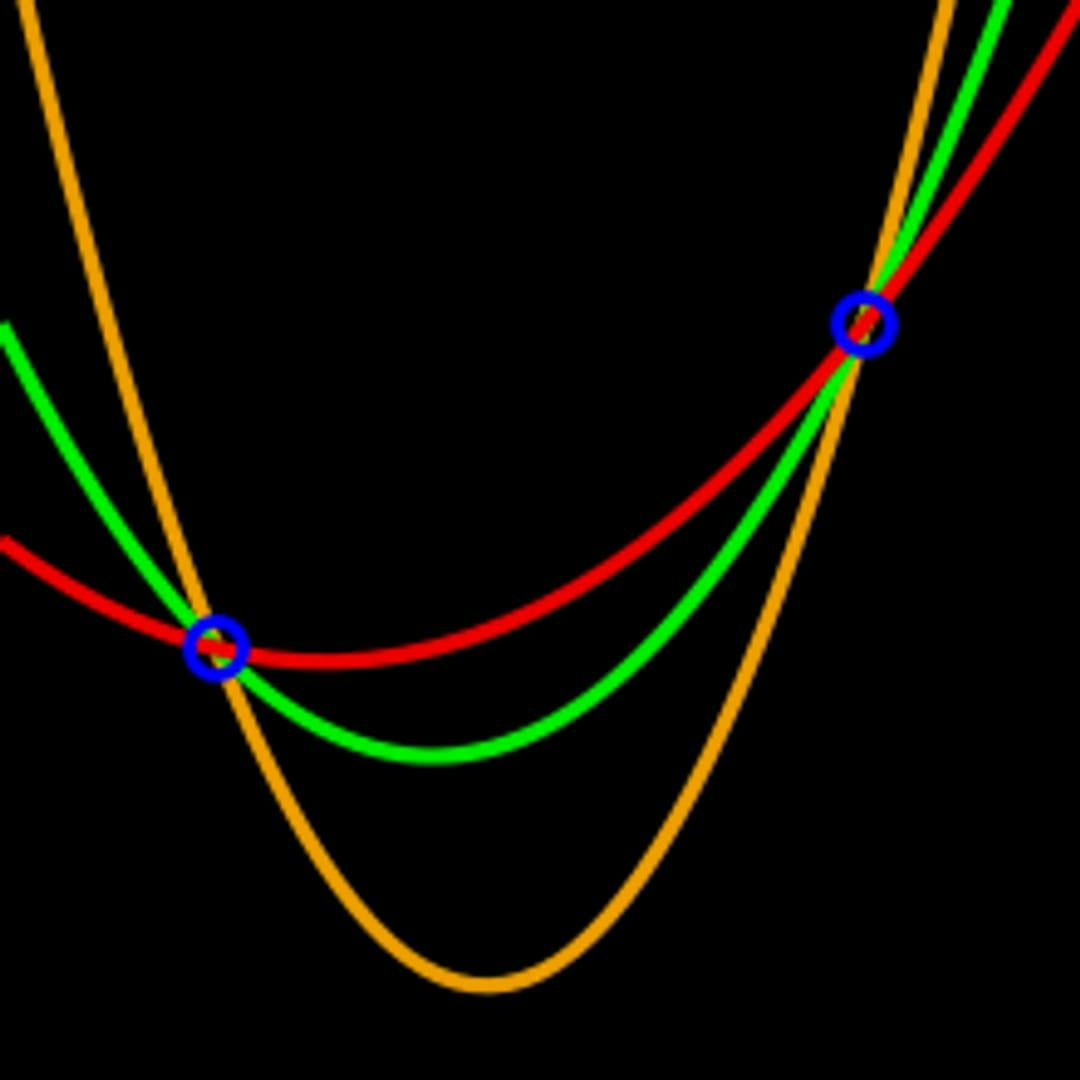

Shamir's Secret Sharing is a popular scheme. In contrast to the scheme above, one may recover the secret with any out of shares instead of requiring all . Based on the Lagrange interpolation theorem, the essential idea is that points are enough to uniquely determine a polynomial of degree less than or equal to . For instance, two points are sufficient to define a line, three are enough to represent a parabola, and so on. The method is to create a polynomial of degree with the secret as the first coefficient; pick the remaining coefficients randomly. Then, find points on the curve and give one to each party. When at least out of the parties reveal their points, there is sufficient information to fit a th degree polynomial, with the first coefficient being the secret. If this is unclear, see this blog post for an alternate explanation.

Each MPC node receives only one PK share and uses it to construct partial transaction signatures to broadcast to the network. Even if a node is offline, loses PK access, or is malicious, it is still possible to reconstruct the complete transaction from the remaining nodes.