Thinking in Systems Summary

The following summarizes Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows.

A system is a set of elements that is coherently organized and interconnected in a structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors (its "purpose”). Systems are typically hierarchical, creating subsystems within systems.

System behavior revolves around stocks and flows. Stocks are elements that can be accounted for at any given time or things that you can see or touch. Flows are the changes in stocks over time. To increase a stock, decrease its outflow rate or increase its inflow rate.

The size of a stock and its changes can affect the inflow and outflow of a system, resulting in feedback loops. Feedback loops can affect only future behavior; they can’t deliver signal fast enough to correct behavior that drove the current feedback.

There are two types of feedback loops. A balancing feedback loop is stabilizing, goal-seeking, and regulating. It’s also called a "negative feedback loop” because it opposes, or reverses, whatever direction of change is imposed on the system. A reinforcing feedback loop amplifies or enhances. It’s also called a "positive feedback loop” because it reinforces the direction of change, creating either vicious and virtuous circles (it reminds me of Amazon’s flywheel).

In physical, exponentially growing systems, there must be at least one reinforcing loop driving growth and at least one balancing loop constraining growth, because no system can grow forever in a finite environment.

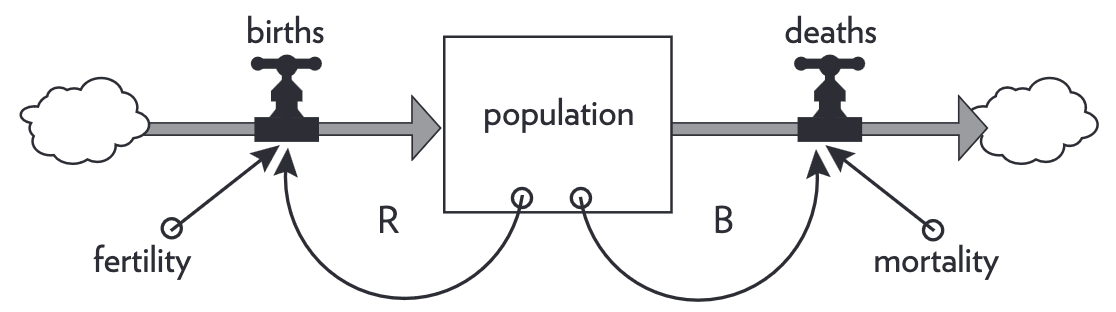

The Earth’s population has births as a reinforcing loop and deaths as a balancing loop.

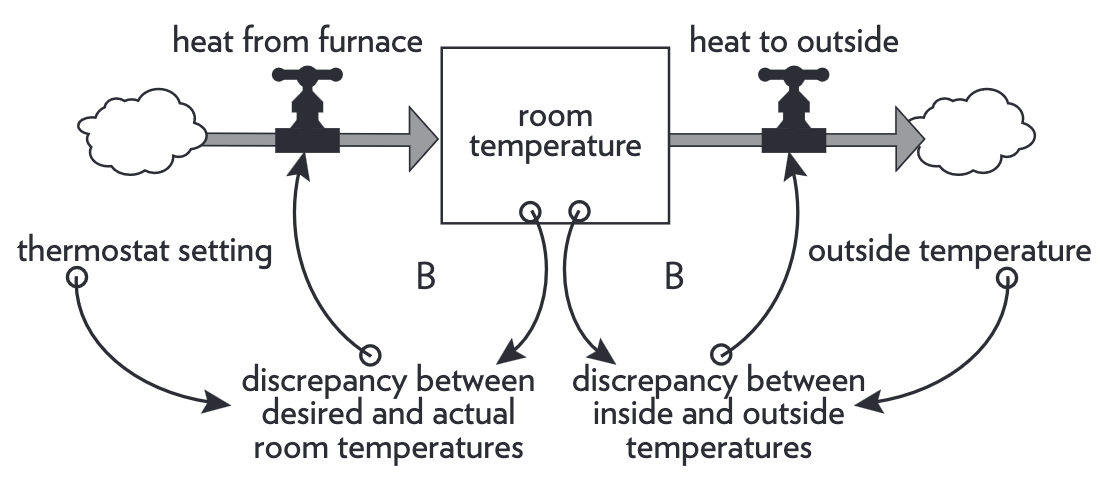

Room temperature is controlled by two balancing loops.

Complex system behaviors often arise as the relative strengths of feedback loops shift, causing first one loop and then another to dominate behavior. Suboptimization results when a subsystem’s goals dominate at the expense of the total system’s goals.

Delays determine how fast systems react, how accurately they hit their targets, and how timely the information is passed around. Changing the length of a delay may have a large change in the behavior of a system. Overshoots, oscillations, and collapses are caused by delays.

Reliance is a system’s ability to recover from perturbation; the ability to restore or repair or bounce back after a change due to an outside force.

Systems contain limiting factors. When one factor ceases to be limiting, growth occurs, and the growth itself changes the relative scarcity of factors until another becomes limiting. To shift attention from the abundant factors to the next potential limiting factor is to gain real understanding of, and control over, the growth process.

Finally, a couple of traps the author calls out:

- Policy resistance occurs when various actors try to pull a system state toward various goals. Any new policy, especially if it’s effective, pulls the system state farther from the goals of other actors with a result that no one likes, but that everyone expends considerable effort in maintaining. To resolve it, seek out mutually satisfactory ways for all goals to be realized or redefine larger and more important goals that everyone can pull toward together.

- Shifting the burden to the intervenor occurs when a solution to a systemic problem reduces or disguises the symptoms, but does nothing to solve the underlying problem. The system can become more and more dependent on the intervention and less and less able to maintain its own desired state; a destructive reinforcing feedback loop. To resolve it, shift the focus from short-term relief to long-term restructuring. Restore or enhance the system’s own ability to solve its problems, then remove yourself.